📢 This week’s journal is structured differently from the others and was inspired by the Nigerian elections held over the weekend. My plan was to dissect issues relating to the Constitution and inclusion, but what you’ll find here is more of a rant—sponsored by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

The Nigerian elections were held this week and, for the first time, I was genuinely excited about the process, the outcome, and the possibility of a shared vision for a New Nigeria. Even though the elections didn’t turn out as I had hoped, I still find myself believing in a better future.

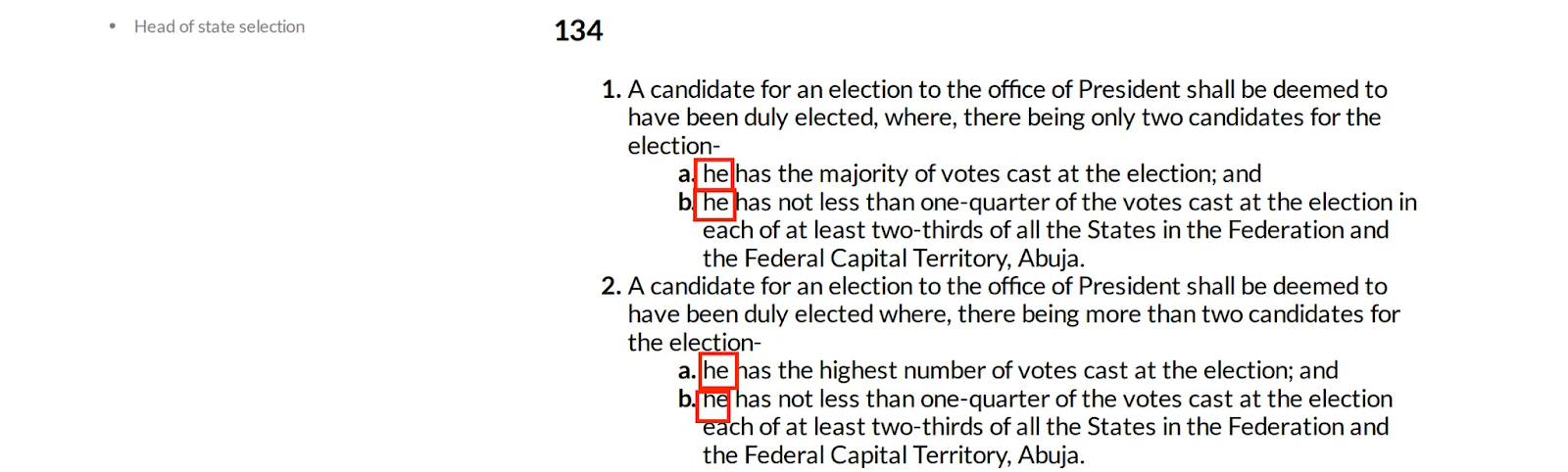

While the nation waited for results to be announced, a snippet of the 1999 Constitution (Section 134) went viral because of its ambiguity on the “success criteria” for electing any candidate.

I’m not a lawyer and I’m not versed in constitutional law, so the legal detail isn’t my focus. Instead, I want to talk about the lack of inclusive language. The Constitution implies that a woman (or a gender-neutral person) cannot be President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

For the purpose of this journal (read: rant), I’ll focus on women, because the same Constitution does not acknowledge fluid gender dynamics and instead often criminalizes them. After reading Section 134, I checked the U.S., South African, Kenyan, and Ghanaian constitutions for good measure—and the difference in language was stark.

It’s such a small detail, but it transported me back to my fictional 13-year-old self—full of hopes and dreams that maybe, just maybe, I could be the first female President. Fast forward to Civic Education class, learning the requirements to become President, and all I saw affirmed that I could never be.

No one said my dreams were invalid. And yet, the Constitution blatantly crushed them with every line. These are formative years for a reason—children are sponges, absorbing everything. A Constitution that implies women cannot hold positions of power ripples outward, shaping how people think about and treat women in society and the workplace.

And yet, some people sat in high offices, drafted this document, reviewed it with their peers, and deemed it “fit.” Later, they would add it to their résumé: “Drafted and shared the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.” Hiss.

As we pray, seek, and hope for a New Nigeria, amending the Constitution is not enough. We must also challenge our beliefs and assumptions. We need to recognize exclusion wherever it exists and take action to undo it.

The Constitution says no citizen should be subjected to any disability, deprivation, or restriction on account of ethnic origin, place of origin, sex, religion, political opinion, or disability. Yet in reality, people are still barred from their shops and homes based on tribe. People with disabilities still face immense challenges to simply belong.

We all have a part to play in building the Nigeria we want to see. Every day, in everything we do, we should challenge our assumptions and biases, and take action toward a more inclusive and equitable country.

Extra inspiration

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: We Should All Be Feminists (opens in a new tab)

First published in my Inclusive Design Journals for the Paystack Design team. Adapted here for this collection.